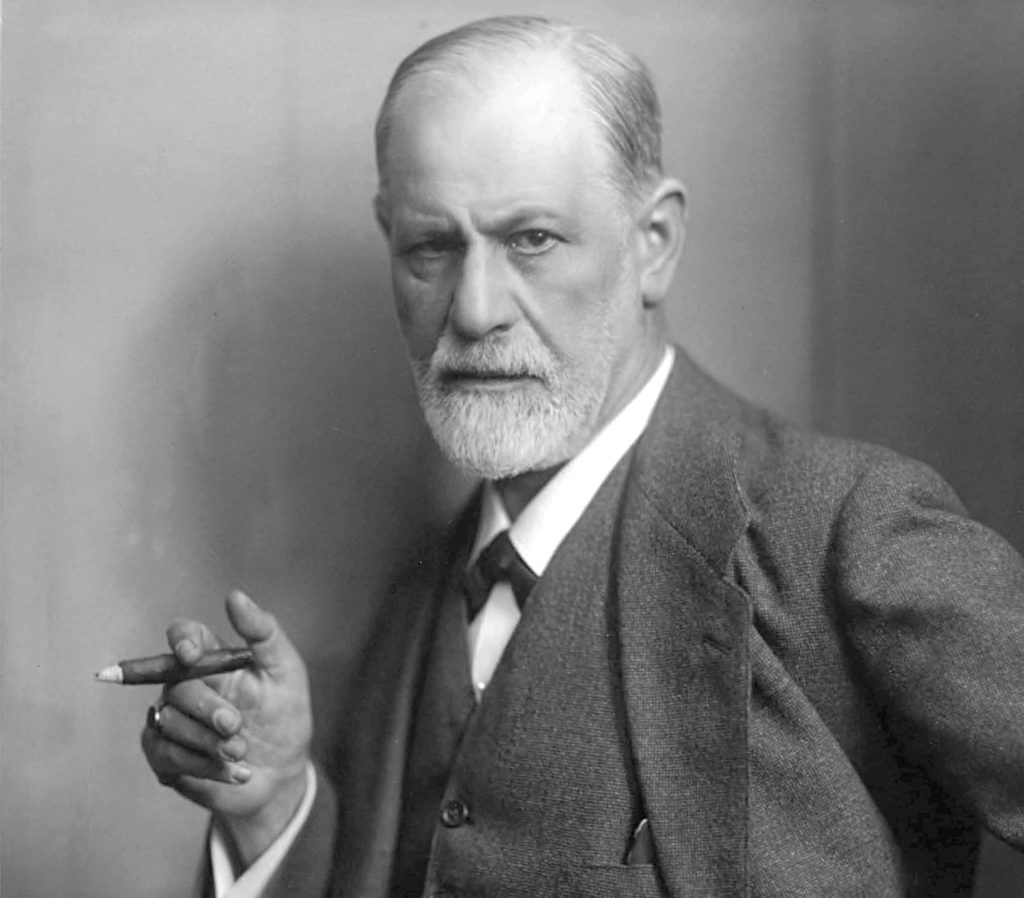

There were few photographs during the Sigmund Freud era, but you’d be hard-pressed to find an image where this father of psychology wasn’t holding a cigar. If you can’t spot a cigar, look closely. On his desk, amid his cherished statues of Eros, the Sphinx, and other gods and goddesses, are the accouterments of a smoker; ashtrays, matches, and cigar boxes.

Sigmund Freud: Early Life

Sigmund Freud was born in Austria in 1856 and attended the University of Vienna. He earned a medical degree in 1881. The following year Freud began work at Vienna General Hospital and conducted his first notable research. After publishing essays on the benefits of cocaine, he followed up with a study of aphasia, on which he later based his first book. This research led to Freud’s appointment as a head lecturer on neuropathy. Soon after, he went into private practice specializing in nervous disorders and developing his theories of psychoanalysis.

Freud started smoking relatively late. He didn’t smoke his first cigar until 24, but it became a routine for the rest of his life. Perhaps the only smoker who rivals Freud’s alleged 20 cigars a day habit was American humorist Mark Twain. When one of Freud’s nephews refused a cigar, he famously told the young man, “Smoking is one of the greatest and cheapest enjoyments in life, and if you decide in advance not to smoke, I can only feel sorry for you.”

Smoking and Work

Freud was a workaholic. Not only was he an innovative thinker who regularly saw patients, but he was a prolific writer and lecturer. Still, Freud made time for leisure. He went on daily walks, always making a stop at the local tobacconist.

Austria had limited choices of cigars. Freud smoked small locally made Trabuco cigars, but he preferred Reina Cubanas, which he could only get when he traveled. Toward the end of his life, Freud also appreciated Dutch Liliputanos.

Whether at work or on a stroll, Freud smoked incessantly. While they lay on the famous couch, his patients often said the smell of cigars was as distinct as the sound of his voice. Like many artists, writers, and thinkers, Freud felt his ability to work directly related to his smoking habit. He once told his doctor, “I believe I owe to the cigar a great intensification of my capacity to work and a facilitation of my self-control.” Indeed, much of his work encompassed human desires, wish fulfillment, and self-control.

Psychoanalysis and Interpreting Dreams

Freud is best known for his development of psychoanalysis in the 1890s. Inspired by methods of hypnosis his friend and colleague Josef Breuer developed, Freud began cultivating some of his own. One of Breuer’s patients, known as Anna O, would later call it the “talking cure,” a process where the patient spoke freely about symptoms rather than the therapist providing suggestions. Freud would eventually call this free association and believed it could access memories in the unconscious that the conscious mind has repressed. Freud believed these were the sources of neurosis and that talking freely could relieve a patient’s symptoms.

The Interpretation of Dreams is perhaps Freud’s best-known work. First, Freud analyzed his dreams along with his patients’ dreams. Then, he introduced the main ideas, such as the Oedipus complex and dreams as wish fulfillment.

Freud and the Pleasure Principle

For Freud, libido was the primary human drive. He often reduced his idea to sex and sexual repression, particularly the relationship between mother and son and father and daughter, but Freud’s concept was much broader. He divided the psyche into the id, ego, and superego to explain human behavior.

He called the human urge to have basic needs met the pleasure principle; It is the driving force behind all human desires and behavior. This pleasure principle extended beyond sex to include hunger, thirst, and plenty of other primal urges. In simple terms, these urges derive from the id, filter through the superego, and present themselves as the ego.

Oral fixations were a focal point of some of his theories. No wonder he was a lifelong cigar smoker. He believed fixations developed in the early stages of psychosexual development. They manifest later in life as habits such as nail biting, gum chewing, and, yes, smoking. Satisfying the pleasure principle is the aim, and Freud did that daily.

As for the famous line “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar,” we’ll never know whether Freud said it. Nevertheless, cigars provided great comfort and pleasure for the father of psychology.

Photo credit: “Sigmund Freud” by cambodia4kidsorg is licensed under CC BY 2.0.